Twice in my life I have been fortunate enough to hear multiple Patek Philippe minute repeaters doing their thing, and the most recent was under interesting circumstances. Patek Philippe is generally, well, you wouldn’t say uncommunicative, but they do have the natural reticence that you’d expect from a family-owned haute horlogerie firm. Let’s go with discreet. However, over the last few years, the company has also begun holding periodic educational seminars, which, though of course they focus on Patek Philippe replica wristwatches and history, also offer a great deal of very useful, generally-applicable information on watchmaking. The last such educational event I was part of was a full-day workshop on static and dynamic poising (which, if you’re of a similar turn of mind to mine, is pretty exciting, white-knuckle stuff, and I’m being totally serious). The most recent, however, was a workshop on minute repeaters, during which we discussed everything from manufacturing gongs, to case construction, to how repeaters are tested and validated for release at Patek – and, yes, horse urine as well; and thereby hangs a tale.

The history of chiming watches is generally pretty well known, at least in broad outline. Telling the time acoustically is the oldest known method, at least in mechanical horology in Europe, and it’s generally thought that the earliest clocks with mechanical escapements had no hands, nor a dial, but rather told the time by ringing a bell. A watch or clock can ring the time either “in passing,” which means that the time is rung automatically at the hours and quarter hours, or “on demand,” which means that the owner can operate a button or slide, and the movement will ring the time at the moment it’s activated.

The word “repeater” means on-demand striking. The first repeaters were English, and the first patent for a repeating watch was granted to Daniel Quare all the way back in 1687. Watches that chime the hour, and the nearest quarter hour, were the first repeating replica watches, and gradually more precise chiming watches were developed, until finally the minute repeater appeared – the very first that we know of were made in Germany, around 1720.

Making minute repeaters at Patek Philippe goes pretty far back. The first one recorded in Patek’s archives was made in 1839, and sold for 450 CHF (it was only the 19th watch produced by the company, at the time). The watch was a quarter repeater. The first half-quarter repeater (which chimes the hour, quarter, and the nearest half-quarter hour, or seven and a half minute period) was sold in 1845, and in the same year the company sold its first true minute repeater too. It was also in 1845 that the first grand et petite sonnerie from Patek was sold (and it was also the year that Jean Adrien Philippe joined the company – big year). Since then Patek has made some of the most famous chiming and complicated watches in the world; it’s a list that includes the Duke of Regla pocket watch from 1910 (grande et petite sonnerie with minute repeater and Westminster chimes, ringing on five gongs), the record-breaking Henry Graves Supercomplication (which we personally witnessed and shared with you as it sold for $24 million in 2014), the Caliber 89, the Star Caliber 2000, and, of course, most recently, the Grandmaster Chime.

The company’s first wristwatch repeater was a five minute repeater (chiming the hours, quarter hours, and then the nearest number of five minute intervals) made as a ladies’ watch in 1916, in a 27.1mm platinum case. Patek’s first wristwatch minute repeater was sold in 1925 and used a 12 ligne blank from Victorin Piguet, who was a frequent supplier both before and after World War II. This is the famous Teetor watch, made for the American automotive engineer Ralph Teetor, who was blind (and whose inventions include the first cruise control). Repeater production in the 1960s and 70s came to a virtual standstill, although in the 1980s two unique pieces – references 3621 and 3615 – were made. In 1989, however, Patek produced the reference 3974 – a minute repeater with perpetual calendar and moonphase that housed the caliber R 27 Q, with a micro-rotor winding system.

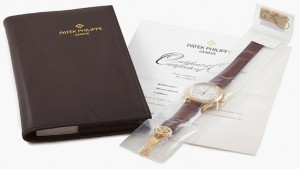

However, it wasn’t until 1992 that Patek Philippe resumed regular production of repeaters (that is, non–limited edition production). The reference 3939, which came out that year, was produced from 1992 to 2010, and it remains one of the stealthiest ways possible to wear a thoroughbred high complication. Back in 2011 Ben described a one-off steel version made for Only Watch: “Reference 3939 has existed in the Patek catalog for some time, but has only been available in gold and platinum. This watch, with a small diameter, hidden tourbillon, enamel dial, and relatively unobtrusive repeater slide is the ultimate silent killer – it may not look like much to the average guy, but boy is it something special.” That particular 3939 ended up hammering for $1.9 million.

Minute Repeater Production At Patek Philippe Today

Patek Philippe has chosen to chart a rather interesting course in minute repeater production in its current collection. While many (well, we’re talking exotic repeaters here, so it’s not that many) companies that are in the repeater business have chosen to push hard on R&D, and make much of technical advantages and advances, Patek is largely still doing things the old fashioned way, although the company has adopted some ancillary testing technology that represents a more modern approach. For instance, recordings of the sound profile of each repeater are made in an anechoic chamber, and the sound is analyzed digitally to ensure that it meets Patek’s internal standards. However, there’s nothing in any Patek Philippe repeater that would seem shocking to a watchmaker from a century ago (in fact, although silicon balance springs are found in many of Patek’s watches, to this day you won’t find them in its repeaters). Despite the undoubted interest in the best of today’s crop of technically forward-looking repeaters, there is something deeply compelling about handling a repeater that represents the continuity of traditional methods you find in a Patek (and which is after all Patek Philippe’s main stock in trade).

Just to provide a little context, it’s useful to remember that working on minute repeaters is demanding in a way that working on other watches is not. The only thing that comes close maybe is the rattrapante chronograph, which, though it also requires great care in both maintenance and manufacturing, doesn’t demand the good subjective judgement for sound quality that is required for the repeater. The horological author Donald de Carle (who was not, to put it mildly, a writer given to hyperbole) writes, in Complicated Watches And Their Repair, that, “It has been constantly stressed that the utmost care must be exercised when repairing complicated watches, and when repairing repeated watches, that advice can now be doubly stressed. We have all heard the phrase, cool, calm and collected, and it can be applied to meet many occasions, but it has a real personal significance to to the person undertaking the care of repeaters…it is for the student to make himself proficient, by acquiring through practice, the mentality necessary to do the work now to be discussed.”

The three primary characteristics of a repeater are the tempo at which it chimes, the quality of the sound, and the volume at which it chimes. Tempo in Patek’s repeaters is controlled by a centrifugal governor, which is underneath the Calatrava cross on the top plate (that’s the part of the movement visible through the display back). There are three gears in series that link the separate spring barrel that powers the repeater to the governor itself, which has two spring loaded arms on it with weights on the end. When you push home and release the repeater slide, you wind the spring barrel, and the speed at which it unwinds – and thus, how fast or slow the chimes ring – is determined by how fast the governor spins. The governor slows the speed of rotation of the mainspring barrel by offering inertial resistance: As it spins, the two arms open outward against the resistance of the springs and slow the speed of rotation, like a spinning figure skater extending their arms (to use a well-worn but illustrative analogy).

Patek started using centrifugal governors in 1989 and they’re now used in all Patek repeaters. The older method for controlling the tempo of chiming is with an anchor, which makes a distinctive buzzing sound; the centrifugal governor is much quieter (though not totally silent). One of the points of adjustment in a repeater is the governor’s speed of rotation – ideally, there is enough power in the mainspring barrel so that the tempo of chiming doesn’t noticeably slow when the last minutes are being struck.

The gongs in a modern minute repeater are generally made of hardened steel; some Patek watches have what are called “cathedral” gongs, which are 1.5 times longer than conventional gongs (and which, based on our experience, have a noticeably deeper and richer sound). Now, despite the relative predictability of modern manufacturing methods, making repeaters remains something of a dark art, and the acoustic qualities of each repeater can vary depending on the properties of the case, movement, dial, and even whether or not the repeater is gem-set, so Patek makes 21 different grades of standard gongs, as well as 21 different grades of cathedral repeater gongs. Gongs are made by hand, one at a time, and learning how to make them is a rather time consuming process – we’re told that, in general, Patek’s watchmakers have to make a hundred or so of a given grade of gong in order to have mastered that type well enough to be allowed to make that grade for actual production minute repeaters. Gongs range from just 0.48mm to 0.6mm in diameter.

Let’s talk about myths and legends for a moment. First of all, we have it straight from Patek Philippe replica that yes, Thierry Stern personally listens to, and approves, each Patek Philippe minute repeater before letting it out into the world. There are four basic stages in the validation process. First, the repeater is approved by the watchmaker who made it. Second, it goes to the anechoic chamber (a room lined with material that suppresses echoes, which would otherwise make for a recording that isn’t clean enough) and a recording is made which undergoes computational analysis for desired parameters. Third, the repeater is listened to by Patek’s senior watchmaker in charge of chiming complications. And, finally, the repeater is sent to Thierry Stern. By the time a repeater gets to Mr. Stern’s office there’s a good chance it will be approved, but very occasionally rejections do occur – not often, according to Patek, but often enough that it’s not just a formality. There are certain basic objective parameters – the sound on average for Patek repeaters is about 60 decibels, the chimes should ring for almost exactly 18 seconds – but a great deal of the vetting process for repeaters is still subjectively done by the human ear.

There are a number of reasons a repeater might be rejected – the hour, quarter, and minute strikes are each evaluated separately, for instance, but they must all work together harmoniously as well. Tempo and volume are also evaluated. We had a chance, as a group, to do a blind evaluation of three different repeaters from recordings made by Patek, and even blind, there was surprising consensus on the quality of each repeater, with several participants able to correctly identify case material, and with virtually unanimous rejection of one watch by our group – and it turns out that this particular watch had been rejected by Mr. Stern as well.

One very interesting point that we discussed extensively is the degree to which case material affects sound. Amongst repeater aficionados, it’s often said that rose gold is the “best” case material in terms of sound quality. While it’s true that rose gold has a characteristic sound profile, it’s not always true that it’s the best in any objective sense. Platinum, for instance, can have a somewhat dull, muted tone, but it can also, at its best, have a kind of crystalline quality you don’t get from a gold case, so a lot of it is really down to personal preference. It’s a bit like the difference between a big Bordeaux and Japanese sake; the latter has a much narrower flavor profile, but within that there are infinite shades of variety and just as surely as there is lousy sake you wouldn’t use to wash out a cat box, and sake that will make you feel like you’re viewing cherry blossoms in spring in the shadow of Mt. Fuji, there are both lousy and terrific platinum minute repeaters.

Another very interesting fact is that consensus was nearly universal that some of the clearest, most beautifully resonant sound came from two of the smallest watches we saw: the references 7002/450G Four Seasons Symphony and the wonderful 7000R Ladies First repeater. I knew the sound of the Ladies First repeater from earlier listening, but I hadn’t heard the Four Seasons Symphony before, and the sound was exceptional – similar, oddly enough, in some respects to the sound from the reference 5073R, which, like the 5073P, has cathedral gongs. The presence of diamonds definitely seems to have an impact on the color of the sound, apart from considerations of size, case material, and movement characteristics.

Oh, about the horse urine – that’s actually a dead serious part of minute repeater history. The story one hears is that one of the trade secrets for making repeaters is that the final quenching of the gongs took place in that particular liquid back in The Good Old Days. To put it in context, throughout the history of metallurgy there have been stories of exotic substances used to quench and temper steel, up to and including human blood, which was supposedly used for the best Damascus steel.

I asked Patek’s master watchmaker in New York Laurent Junod about this piece of possible horological apocrypha and he said that it was absolutely true. It turns out that urine has been a favored substance for quenching steel for centuries, thanks to its ammonia content – ammonia contains nitrogen, and there’s a process called nitriding, which produces something known as a case-hardened surface in steel, and if you think I’m blowing smoke, you can read all about it in “The Effects Of Human And Animal Urine On Nitriding For Improved Hardness Property Of Aluminum Alloy Materials” in the European Journal Of Material Sciences (which talks about nitriding steel as well).

can’t get anywhere else. Undoubtedly, you’re disappointed to have come to the end of this story without a single recording of one of these watches, no? Fortunately we have something quite extraordinary to share with you again – in 2013 we recorded what was then the entire Patek Philippe minute repeater collection and you can jump back in time and have a listen again to something really extraordinary here.

In an horological world where new and better are constant buzzwords, it’s great to see such old-school watchmaking still going on at this level. There is absolutely nothing wrong with blazing new trails and advancing horological science but to see to this day what you can get out of absolutely classic methods and materials provides a connection to the history of watchmaking at its best, not easily obtained elsewhere.

And, as a bonus, here’s our exclusive video coverage of one Patek chiming complication that wasn’t part of the presentation I attended: the quality Patek Philippe replica Grandmaster Chime, reference 5175R, made to celebrate Patek’s 175th anniversary. Oh, and if your ears don’t get too tired, why not treat yourself to the video we put together that time we went hands-on with the Henry Graves Supercomplication – that’s right, you can hear it do its thing too.

c

c